Syria: Robert Fisk reports from the front lines

A poster in Nubl featuring Vladimir Putin, Bashar al-Assad and the Hezbollah leader Sayed Hassan Nasrallah (Nelofer Pazira)

The following reports from the front lines of the war against Syria appeared online at the end of last month. Written by the veteran English journalist and author ROBERT FISK of the London Independent, they stand out from the media chorus orchestrating the disinformation of Obama and the Trudeau Liberals, who are claiming to support a “moderate opposition” in a “civil war” to justify their own intervention and warmongering against the Syrian Arab Republic and its allies. They are hysterically blaming the Syrian and Russian forces for “besieging” Aleppo, the economic and industrial heartland of Syria, and other Syrian cities and towns forcibly held hostage by terrorist forces cobbled together primarily by Saudi Arabia, Turkey and Jordan, instigated by the secret services of the United States, France, Britain, Qatar and others, including Canada. The Molotov cocktail of terrorist gangs is their creation. Under the cover of “talks” and humanitarian gestures, they are frenziedly escalating the delivery of arms, deploying new forces for “training” and reorganizing their broken proxy forces.

Canadians are denied essential information about the real nature of this five-year-old conflict, which has caused so many lives. The number of Canadian journalists who have actually visited Syria during this period can be counted on one hand. I know of but five, three of whom are independent including this writer, and who travelled on the basis of their own resources. As a result, Canadians do not even know what they do not know.

This weblog is circulating the reports of Robert Fisk as part of our ongoing series of information updates to assist our readers as well as the anti-war forces to maintain their orientation against the massive disinformation coming from the monopoly media, including the CBC and CTV. In contrast, although Fisk refers to an elected secular government as “regime” and replicates some of the sectarian viewpoints characterizing the conflict as religious in nature, he brings out some features of the real forces in combat and portrays a “human face” and the resistance of the valiant people of Syria, their soldiers and allies against a barbarous aggression that as caused enormous tragedy.

The use of force to solve political issues and justify foreign intervention is unjustifiable. We reiterate our categorical opposition to a U.S. attack against Syria, or by any other country. Collusion by Canada under the pretext of “democracy,” “peacekeeping” and “saving refugees” is unacceptable and cannot be conciliated with. – TS (Note: Some photos have been added.)

The ‘untold story’ of devastating siege and resistance of the two villages of Nubbul and Zahraa

Syrian volunteers aged 50 to 70 in the northern towns of Nubl and Zahra are fighting against forces opposing the Syrian government

Robert Fisk, talks about the suffering of the two liberated towns of Nubbul and Zahraa in Syria’s Aleppo besieged by Takfiri terrorists for about three years. Villages that remained loyal to the Syrian government have paid a steep price.

The Independent (Feb. 22) – This is the untold story of the three-and-a-half-year siege of two small Shia Muslim villages in northern Syria. Although their recapture by the Syrian army – and by Iranian Revolutionary Guards and Iraqi Shia militias – caught headlines for a few hours three weeks ago, the world paid no heed to the suffering of these people, their 1,000 “martyrs”, at least half of them civilians, and the 100 children who died of shellfire and starvation.

The Independent (Feb. 22) – This is the untold story of the three-and-a-half-year siege of two small Shia Muslim villages in northern Syria. Although their recapture by the Syrian army – and by Iranian Revolutionary Guards and Iraqi Shia militias – caught headlines for a few hours three weeks ago, the world paid no heed to the suffering of these people, their 1,000 “martyrs”, at least half of them civilians, and the 100 children who died of shellfire and starvation.

For these were villages that remained loyal to the Syrian regime and paid the price – and were thus unworthy of our attention, which remained largely fixed on those civilians suffering under siege by government forces elsewhere.

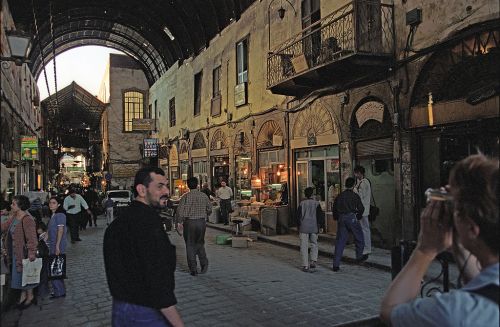

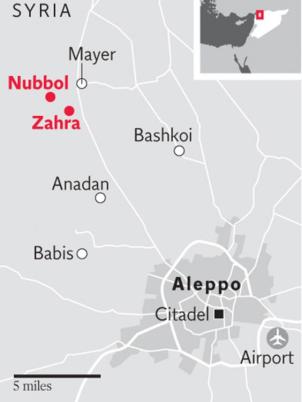

Nubl and Zahra should be an 18-minute drive off the motorway north-east of Aleppo but the war’s front lines in the sharp-winded north of Syria have cut so deeply into the landscape that to avoid the men of the Jabhat al-Nusra and Isis, you have to drive for two hours along fields and broken country roads and through villages smashed and groined by the Syrian offensive.

Syrian and Iranian flags now hang from telegraph poles outside the damaged village mosques, a powerful symbol of an alliance that brought these people’s years of pain to an end. Among them were at least 100 Sunni Muslim families – perhaps 500 souls – who, way back in 2012 chose to take refuge with their Shia countrymen rather than live under the rules of the Islamists.

On another occasion, they threatened to shower us with chemical weapons.

The police commander, Rakan Wanous, kept meticulous records of the siege and deaths in Nubl and Zahra and recorded, with obviously bitter memories, the threatening phone calls he took from the Nusra forces surrounding his two villages. Wanous was also officially in charge of many other towns that had fallen to Nusra. Yes, he said bleakly, the calls came from the neighbouring Sunni village of Mayer. “Once, they told me they were going to come and slaughter us – and slaughter me – and I told them: ‘Well, let’s wait until you get here and see.’ On another occasion, they threatened to shower us with chemical weapons.”

Wanous was deeply upset in recalling this. Had some of the calls came from people he knew personally? I asked. “Yes”, he said. “The ones who threatened me often were from my own police force. They came from my own policemen – of course, they had my mobile number. Some calls came from sons of my own friends.” Of Wanous’s 15‑man police force, five stayed loyal to him. The other 10 defected to Nusra.

From the start, Nubl and Zahra were defended by their own pro-regime militiamen, a force perhaps 5,000-strong who were armed with rifles, rocket launchers and a few mortars. Up to 25,000 of the original 100,000 civilian inhabitants managed to flee to Turkey in the early days of the fighting. The rest were trapped in their homes and in the narrow, shell-blasted streets. “We reached a period after a year when we were in despair,” one of the local civil administrators, Ali Balwi, said. “We never expected this to end. Many of the civilians died because their wounds could not be cared for. We ran out of petrol early on. They cut off all electricity.”

The villages’ sole link with the outside world was the mobile phone system that operated throughout the siege so that civilians and militiamen could keep in touch with families and friends in Aleppo. Mohamed Nassif, a 61-year old civil servant, recalled how he had, in desperation, called the UN in New York to plead for help and humanitarian aid for the villages. “I spoke to someone – he was a Palestinian lawyer – at the UN Human Rights office in New York and I asked if there was any way the UN could lift this siege and help us. I asked for humanitarian aid. But they did nothing. I did not hear back from them.”

When the siege began, Wanous said, the Syrian government resupplied the villagers with food, bread, flour and medicine. The helicopters also dropped ammunition. There were three or four flights every day during the first year. “Then at about five o’clock, at dawn, on 30 June 2013, a helicopter came to us with some returning villagers from Aleppo and a staff of seven teachers for our schools who were to hold the school exams here,” Wanous said. “Someone in Mayer fired a rocket at the helicopter and the pilot managed to steer it away from the village and it crashed on the hillside outside in a big explosion. There were 17 on board, including the pilot and extra crewman. Everyone died. The bodies were in bits and all were burnt. That was the last helicopter to fly to us.” The wreckage of the helicopter still lies on the hillside.

Terrorists attack the headquarters of government forces in the villages of Nubul and al-Zahraa in Aleppo, Syria Getty

But there were Syrian Kurdish villages to the north of Nubl and Zahra and Kurdish fighters from Afrin tried to open a road to the besieged Shia; yet Nusra managed to block them. So the Kurds smuggled food to their Syrian compatriots by night. There are differing accounts of what happened next. Some in the village admitted that food prices became so high that poor people could not afford to eat. The authorities say that at least 50 civilians died of hunger. Fatima Abdullah Younis described how she could not find medicine for her sick mother – or for two wounded cousins who could not be cared for and died of their injuries. “God’s help was great for us and so we were patient,” she said. “But we suffered a lot and paid a heavy price in the blood of our martyrs.” During the siege, Ms Younis learned that her nephew, Mohamed Abdullah, had been killed in Aleppo. She and her husband have lost 38 members of their two families in the war.

But the war around Nubl and Zahra is far from over. I drove along the route from Bashkoi, which the Syrian and Iranian forces took to reach the villages, and found every house, mosque and farm destroyed, the fields ploughed over, olive trees shredded by the roadside. Big Russian-made tanks and trucks carrying anti-aircraft guns blocked some of the roads – driven in one case by Iraqi Shia militiamen with “Kerbala” written on their vehicle – and just to the east of one laneway a Syrian helicopter appeared out of the clouds and dropped a bomb on the Nusra lines half a mile away with a thunderous explosion and a massive cloud of brown smoke. Ramparts of dark, fresh earth have been erected alongside many roads because snipers from Nusra and Isis still shoot at soldiers and civilians driving out to Aleppo.

There seemed no animosity towards the Iranians – whose battledress is a lighter shade of camouflage than the Syrians and whose weapons and sniper rifles seem in many cases newer and more sophisticated that the old Syrian military Kalashnikovs – and you had to talk to the families in Nubl and Zahra to understand why. Many of them had visited the great Iranian shrines in Najaf and Kerbala and several women, including Fatima Younis, had sent their daughters to Tehran University. One of her daughters had – like other young women from the villages – married an Iranian. “One of my daughters studied English literature, the other Arabic literature. My Iranian son-in-law is a doctor,” Younis said. So, of course, when the Iranians arrived with the Syrians, they were greeted not as strangers but as the countrymen of the villagers’ own brothers-in-law.

“The foreign forces came to us because they felt our suffering,” Younis said. “We appreciated their sacrifices. We are proud of them for helping us. But we are Syrian and we have loyalty for our country. . .”

“The foreign forces came to us because they felt our suffering,” Younis said. “We appreciated their sacrifices. We are proud of them for helping us. But we are Syrian and we have loyalty for our country. We knew that God would help us.” But what of their Sunni neighbours? One old woman holding a grandchild in her arms said it would be “very difficult” to forgive them, but her younger companion was more generous. “Before the attacks, we were like one family,” she said. “We didn’t expect we would ever have a problem in the future. But we are simple people and we can forgive everybody.”

There was no sign of Hezbollah fighters in the villages, although everyone said they accompanied the Syrians and Iranians into the battle. But there was one imperishable sight on the walls: a newly minted poster showing the faces of Vladimir Putin, President Bashar al-Assad and Sayed Hassan Nasrallah, the Lebanese Hezbollah leader. Rarely, if ever, have the forces of Russian Orthodoxy, the Alawite sect and Shia Islam been brought so cogently together.

The men who defended Nubl and Zahra – they also used a B-9 rocket launcher to shoot at Nusra – at first called themselves the “National Defence Force” and then just the “National Defence”. It remains unclear whether they were partly made up of pro-government militias – although such units scarcely existed in this region at the start of the war. The police commander, Rakan Wanous, is an Alawite – or, as journalists always remind readers, the Shia sect to which Assad belongs. Indeed, he is the only Alawite in the area.

A poster in Nubl featuring Vladimir Putin, Bashar al-Assad and the Hezbollah leader Sayed Hassan Nasrallah (Nelofer Pazira)

On the front line with the Iranian Revolutionary Guards battling outside Aleppo

Independent (Feb. 23) – We knew who they were the moment they approached us on the front line outside Aleppo. The Iranian Revolutionary Guards – no longer merely advisers but fighting troops alongside the Syrian army – emerged on the roadside in their grey-patterned camouflage fatigues, speaking good though not perfect Arabic but chatting happily in Persian when they knew we could understand them.

Syrian government forces cross a retractable military bridge on the outskirts of Aleppo | Getty Images

Why, they asked politely – they were courteous, but very suspicious in the first few minutes – were we filming this part of their line? A mortar exploded in a field to our right – sent over either by “ISIS” or by Jabhat al-Nusra – and we had filmed its cloud of brown smoke as it drifted eastwards.

I told the Iranian commander, a tall, bespectacled and thoughtful man, that we were journalists. I got the impression that these men wanted to talk to us – which proved to be the case – but they were wary of us, as if we were dangerous aliens.

“When I heard that there was an English reporter asking for information in this area,” the man said, “I said to myself: ‘England is helping “ISIS” and an English reporter is here asking for information’. The immediate thing in my mind was, ‘Where is this information going to go?’”

He apologized. We must not think he was hostile to us. “If you were in my place and you were fighting a harsh and brutal enemy like “ISIS” in this location – and this is our front line – you would ask yourself this question: ‘What is the English reporter doing here – why should he be allowed here?’”

We explained that we were travelling with Syrian military personnel, and I showed the Iranian commander my press card – and he recognized my name and newspaper. There was much shaking of hands. The Independent was respected, he said. But he was still a very cautious man.

Down the dun-colored road in front of us, across the flat plains to the south-east where the Nusra and Isis lines still held against the Syrian advance, there was an awful lot of rifle fire and the sound of bullets whizzing past the buildings. Outgoing, the Iranians assured us – I’m not sure I believed them, suspecting the fire was coming from their enemies – but the shooting continued throughout our strangely existential conversation.

“One of the problems of this place is that the enemy is very close,” the Iranian said, pointing through the dust haze. “You see those two silos over there? Well, that’s where Nusra are sitting right now and watching us at this moment. Any time, a mortar can arrive, you will be dead – and I will feel responsible, because in the last few hours I have already lost one man and had another wounded.” We were not there to die, I told the man. Reporters have to live to tell their tale.

“One of the problems of this place is that the enemy is very close,” the Iranian said, pointing through the dust haze. “You see those two silos over there? Well, that’s where Nusra are sitting right now and watching us at this moment. Any time, a mortar can arrive, you will be dead – and I will feel responsible, because in the last few hours I have already lost one man and had another wounded.” We were not there to die, I told the man. Reporters have to live to tell their tale.

He grinned at us. “We make a distinction between death and martyrdom,” he said. “In my view, because you are here and seeking the truth and bringing that truth to the world, if you die here in this spot, you are a martyr.”

The comment was intended to be kind. He was allowing a non-Muslim to become a martyr – which I had no intention of becoming. I told him how I had the very same conversation during the 1980-88 Iran-Iraq war in a trench opposite Saddam’s front line. A soldier then had told me of the pleasure he would experience in dying for Islam and I had told him it was my intention to live, that death held no joys for me. Never the twain shall meet, I said to myself.

The Iranian officer – and seven others had gathered round him in the hot afternoon, the crack and zip of bullets still breaking up our conversation – insisted that “to fight in the way of justice is martyrdom”. But then a team of Iranian military IT men arrived, serious, courteous, and wanted to look at our camera. They looked at the pictures of the mortar explosion and concluded that we were telling the truth – we were not spies. They were frightened that we had filmed their own strategic locations.

Then another younger man arrived, bearded but smiling broadly. “This is not the right place for you to be,” he said. “If you want to show the truth of what is happening, you should go to the north of Aleppo and you should see villages and how they’ve been destroyed and how those who rejected the rule of al-Nusra were treated. They have lost everything – their homes have been smashed – and even if the war was to end now, the clean-up and preparations to rebuild will take at least a decade. That’s how badly damaged everything is.”

I realized at that moment that this young man must have fought to retake the Shia villages of Nubl and Zahra with other Revolutionary Guard forces three weeks earlier.

“You should understand the kind of suffering these people have gone through – that’s what you should be writing about,” he said.

“You should understand the kind of suffering these people have gone through – that’s what you should be writing about,” he said. He looked at us to see if we understood, and I suspect that for him this was a holy as well as a military mission – which may not be quite the way to win a war. But there they were, the Iranians in Syria chatting away to us on the battlefield – the “real thing”, as journalists like to say – and we took our leave.

“We would like you to write the truth about this place,” the commander said. “And I’m sorry we can’t allow you to see our lines.” There were more smiles from yet more Iranians who had turned up on motor cycles and in Toyotas. And then the commander went to his vehicle and came back with a large box of Arab sweets and handed them to us. How very Iranian of him. England supports “ISIS”, it seems, but he was ready to feed the English reporter on his front line. But please, no more pictures.

They are sending home Iranian bodies at the rate of 10 a week from Aleppo military airport. Quite a price.

State-of-the-art technology gives President Assad’s army an edge

The government has lost over 60,000 men since the war began, but new Russian equipment is helping turn the tide

The Independent (Feb. 27) – You can see the Syrian army’s spanking new Russian T-90 tanks lined up in their new desert livery scarcely 100 miles from Isis’s Syrian “capital” of Raqqa.

There are new Russian-made trucks alongside them, and a lot of artillery and – surely Isis’s spies are supposed to see this – plenty of Syrian soldiers walking beside the perimeter wire beside Russian soldiers wearing floppy military hats against the sun, the kind they used in the old days in the summer heat of Afghanistan in the 1980s. There’s even a Russian general based at the Isriyah military base, making sure that Syrian tank crews receive the most efficient training on the T-90s.

No, Russian ground troops are not going to fight Isis. That was never the intention. The Russian air force attacks Isis from the air; the Syrians, the Iranians, the Afghan Shia Muslims from north-eastern Afghanistan, the Iraqi Shias and several hundred Pakistani Shias must attack Isis and Jabhat al-Nusra on the ground.

But the Russians have to be up in the desert to the east of the Aleppo-Hama-Homs-Damascus axis, both to train the Syrian tank crews and maintain an eastern base of forward air controllers to guide the Sukhoi bombers on to their night-time targets.

Everyone on the Syrian front lines will tell you that the Syrian air force bombs its enemies only in clear weather. When the winter clouds descend and the rain falls across northern and eastern Syria, the Russians take over.

“The Syrians are low enough to see – the Russians, when they come, you never see them,” as one constant visitor to the war fronts put it with military simplicity. No wonder senior Russian officers are now also attached to the Syrian army command in Aleppo. Vladimir Putin doesn’t do things by halves.

Yet the most important military support the Russians have given to the Syrians is not the tanks – impressive though they look – but the technology that goes with them.

Syrian officers have been shown how the new T-90 anti-missile system causes rockets to veer off course only yards from the tanks when fired directly at them. Is this the weapon that might defeat the mass rocket assaults of Isis and Nusra? Perhaps. Even more important for the Syrians, however, are the new Russian night-vision motion sensors, and the electronic surveillance-reconnaissance equipment which enabled the government army to smash through the Nusra defences in the mountainous far north-west of Syria, breaking the rebel supply lines from Turkey to Aleppo.

In an army that has lost well over 60,000 dead in almost five years of hard fighting, Syria’s officers have suddenly discovered that the new Russian technology has coincided with a rapid lowering of their casualties. This may be one reason for the steady trickle of old “Free Syrian Army” deserters back to the ranks of the government forces, depleting even further David Cameron’s 70,000-strong army of “moderate” ghost soldiers. Intriguingly, since the start of the war in 2011, a far higher percentage of Syrian police and political security personnel have gone across to Bashar al-Assad’s enemies than have soldiers in the regular army. There have been 5,000 security personnel defections out of a total force of 28,000 police.

The Russians are in a unique position among Syrian ground forces; they can train the Syrians how to use the new tanks and then watch how the T-90s perform without having to suffer any casualties themselves. Originally, there were plans to recapture Palmyra, the Roman city already partly vandalised by Isis, but the difficulties of the flat desert terrain have persuaded the Syrians that offensives in the north to cut off all rebel routes from Turkey into Syria will be far more worthwhile.

No wonder the Turks are now laying down shellfire amid Syrian forces along their mutual border. The Russians, of course, find it far easier to train men to fight in cities or mountains – environments in which they themselves have fought – than in deserts, in which no Russian military personnel have had experience since Gamal Abdel Nasser’s war in Yemen.

The offensives that retook the Shia villages of Nubl and Zahra last month were of great interest to the Russian military. For the first time, Syrian army Special Forces, Iranian Revolutionary Guards and Lebanese Hezbollah fighters operated together with Syrian tanks and helicopters, blasting their way through 20 miles of villages and open countryside in just eight days.

. . . the statistics of foreign forces fighting for the Syrian regime appear to have been grossly exaggerated in the West

But the statistics of foreign forces fighting for the Syrian regime appear to have been grossly exaggerated in the West. There are fewer than 5,000 Iranian Revolutionary Guards in Syria – this includes advisers as well as soldiers – and the other 5,000 foreign fighters include not only Afghans and Hezbollah but Pakistani Shia Muslims as well.

Despite all the boasts of Saudi Arabia that it has formed a massive, if hopelessly untrained, “coalition against terror”, it seems that the Syrians, Iranians and Hezbollah have managed to operate together in difficult, rainy terrain and win their first major joint battle. Iranian forces are now being used on the front lines for the first time, principally around Aleppo. Their first advance began in the south Aleppo countryside in November. Officially, they and the Syrians were said to be planning to open the old international highway from Aleppo to Hama, but the real plan was to break the sieges of the Shia villages of Fuah and Kafraya.

In the eastern countryside, Colonel Suheil Hassan, the “Tiger” whom some of the Syrian military regard as their Rommel, has been heading north to end an Isis siege on a Syrian airbase.

But what of the Kurds, whose advance southwards has also endangered those rebel supply routes to Aleppo? The Syrians are grateful for any Kurdish help they can get. But few in the military have forgotten the chilling events of 2013, when retreating Syrians sought refuge with Kurdish forces after the battle for the Mineq airbase. The Kurds demanded a vast tranche of weapons from the Syrian army in return for their men – soldiers for ammunition – in which millions of rounds of AK-47 and machine-gun ammunition and thousands of rounds of rocket-propelled grenades were sought in return for the release of the soldiers.

But the Kurds wanted to persuade Nusra to return Kurdish prisoners, and offered the senior Syrian officers from Mineq to Nusra in return for the captives. Nusra agreed, but once the Kurds handed over the Syrian officers, the Islamist rebels – who had lost around 300 of their own men in the Mineq battle – at once killed all the Syrian officers the Kurds had given them, shooting them in the head.

Among them was the acting Syrian commander at Mineq, Colonel Naji Abu Shaar of the Syrian army’s 17th Division. Events like these will not endear the Kurds to the Syrian army in future years.

Meanwhile, the Syrians continue to lose high-ranking officers in battle. At least six generals have been killed in combat during the Syrian war, allowing the army to proclaim that their top men lead from the front.

The commander of Syria’s Special Forces was killed in Idlib, and the commander of Syrian military intelligence in the east of the country was killed in Deir al-Zour. Major-General Mohsen Mahlouf died in battle near Palmyra. General Saleh, a close friend and colleague of Colonel “Tiger” Hassan, took on the suicide bombers of al-Qaeda in the Sheikh Najjar Industrial City outside Aleppo a year ago.

He told me that suicide bombers killed 23 of his men in one vast explosion there. I met him afterwards, and thought at the time that he had adopted a blithe – almost foolhardy – disregard of death. Just a month ago, he drove over an IED bomb which blew off the lower half of his right leg. These are hard men, many of whom trained in a Syrian military college whose front gate legend reads: “Welcome to the school of heroism, where the gods of war are made.” Chilling stuff.

Syrian civil war: On the road to Aleppo – where people have abandoned all in the shadow of Isis

You will learn a lot about Syria’s tragedy driving between Damascus and the ancient city – and you must drive fast

Independent (Feb. 20) – You can drive these days from Damascus to Aleppo but the road is a long one, it does not follow the international highway and for almost a hundred miles you whirr along with Isis forces to the west of you and, alas, Isis forces scarcely three miles to the east of you.

The moral of the story is simple: you will learn a lot about Syria’s tragedy on the way, and about the dangers of rockets, bombs and IEDS, and you must drive fast – very fast – if you want to reach Syria’s largest and still warring city without meeting the sort of folk who’d put you on a video-tape wearing an orange jump suite with a knife at your throat.

The old road north as far as Homs is clear enough these days. Syrian air strikes keep the men from Isis away from the dual-carriageway. But once you’ve negotiated the Dresden-like ruins of central Homs – the acres of blitzed homes and apartment blocks and shops and Ottoman houses, still dripping with broken water mains and sewage – you must turn right outside the city and follow the signposts to Raqqa. Yes, Raqqa, the Syrian ‘capital’ of Caliph Baghdadi’s cult-kingdom where no man – or no westerner, at least – fears to tread. And then you drive slowly through Syrian army checkpoints and past thirty miles of ruins.

These are not the gaunt, hanging six-storey blocks of central Hama. They are the suburbs and the surrounding villages where the revolution began almost six years ago and where it metamorphosed from the ‘Free Syrian Army’ of which Dave Cameron still dreams – all 70,000 of them – into the al-Qaeda-affiliated Jabhat al-Nusra and then, like a Victorian horror novel, into Isis. For all of those 30 miles – perhaps 40 if you count some outlying hamlets in the dust-storms that blow across the desert – I saw only feral children, two makeshift sweet stores and a few still-standing homes. The rest is crumpled concrete, sandwiched roofs, weed-covered and abandoned barricades from wars which no reporter witnessed and of which there is apparently no visual record. They are the homes of the poor, those who had no chance of salvation in their own country.

They are the homes of the poor, those who had no chance of salvation in their own country.

It’s strange how the visual disconnect interrupts you as you speed down the bumpy, pot-holed road. Where have all the people gone, I kept asking myself? Why are those who live here not rebuilding their homes? And then I remembered the thousands of Syrian refugees I saw and met streaming through the hot cornfields of northern Greece last summer en route to Macedonia, and the pictures of those tens of thousands walking the frozen railway tracks north to Germany, and of course it made sense. This is the midden which those people left, the “Ground Zero” they abandoned. This is the empty bedlam which drove them to despair and to Europe. These are not the homes of the internally displaced. They are the homes of those who have abandoned all.

“Raqqa 240 kilometres,” says the official blue road marker which flashes past us, and I look at my driver – his name is Mohamed – and he casts me a look of both humour and palpable unease. Straight north of Hama is the international highway we should have been travelling on, but – I missed all reports of this – Isis has cut this road in several places. So we head on north east on this uneasy road in near silence.

Then the wreckage starts. A burned-out bus on my side of the car – “38 passengers were killed in that bus,” Mohamed says, but he can’t remember if it was hit with rocket-propelled grenades or drove over a hidden mine left for the army. Mohamed’s wife is in the back of the car and points east across the grey desert to a swaddle of concrete two miles to the east. “That’s al-Mabouji,” she says quietly. “Isis went in there six months ago and massacred 65 civilians and took eight women away as slaves. No-one has seen them since.” Another road sign. Raqqa 219 kilometres.

So now we know that Isis is to the west of us on the old highway and that Isis is scarcely three – at the most eight – miles to the east of us. I begin to count the Syrian army checkpoints, teenagers with Kalashnikovs and the Syrian flag flying over their concrete huts. This is how the government keeps the road open – conscript soldiers and a series of flying columns, open-top trucks mounted with heavy machine guns and soldiers cowled behind scarves to protect them from the desert wind. Most of the transport trucks are travelling in convoy – patrols at both ends – and a military column races down the road towards Homs, trucks and armour with rifles pointing like hedgehog quills from the military lorries.

There’s another village close by – Khanaifis – which Isis shelled several weeks ago in an attempt to cut our road, killing 45 civilians, mostly women and children. “Raqqa”, says the next infuriating sign. “167 kilometres”. And I remember that somewhere over there to the east, on grey sand looking identical to the stony earth around us, Isis put to death those poor Western men on the videotapes with knives to cut their heads off. The Syrians have built little fortresses beside the highway now, tiny castles of sand and concrete sprouting with machine guns, a few Katyusha batteries and an occasional tank. It becomes an obsessive task to count these little protective ramparts. Could they really disgorge a Syrian version of the US Cavalry if the black flags of Isis suddenly appeared on the road? The black flags did appear about a month ago but the Syrians drove to the road-block and killed every armed member of the world’s most fearful cult.

One of Syria’s top soldiers, General Suhail, known to most Syrians as “The Tiger” – he is now fighting in the eastern desert far from here – blasted our two-lane highway open two years ago and relieved the siege of Aleppo and now it trails across the desert like a single spider’s thread, a lifeline for the government and its supporters. That’s why it’s called the ‘Military Road’. There’s another burned-out, overturned bus on the right and a scattering of rusting oil tankers hit by rockets. The passenger coaches that now race past us have their curtains pulled, just like the old buses in Afghanistan when the Taliban were on the hunt for victims.

We pass a village where there were four suicide car bombs – the place is now swamped with armour and police cars – and then the countryside lights up and turns green and the fields are dark with fresh earth and women working in the strawberry fields and an old railway track with all but 20 feet of track stolen by theives. And we drive into Aleppo, the place still thumped by the sound of shellfire – outgoing, from the Syrian army, which is now winning ground around the city – and I see a railway bridge behind which I hid with Syrian soldiers two years ago from night-time snipers.

No longer. The city is reborn. There are smart military policemen in red berets on the checkpoints, new shops opened beneath crushed apartment blocks, and the sound of incoming shellfire and ambulances driving painfully through the traffic jams. Who would believe we could be so happy to see this dangerous old city and its burned medieval market and decrepit hotels? Now that tells you something about the war in Syria.

Syrian soldiers on the Latakia Front finally taste the fruits of victory – but they know Isis is not dead

Can Syria be put back together again? Its army is in the habit of talking again about a future state with all its borders intact

Independent (Feb. 18) – Along the Syrian army gun line, they are firing their 130mm artillery out of the wooded valleys south of Kassab, the guns invisible amid the hot orchards and the dark trees.

And from the smashed village of al-Rabiaa – newly taken by the Syrian army from the retreating rebels of Jabhat al-Nusra – you can watch the shells exploding across the valley, a great curtain of blue smoke that ascends into the heavens just this side of the Turkish border.

The guns whack out their shells every 30 seconds and they soar over us and, six seconds later, you can see the impact of their explosions through the heat haze. A Syrian colonel watched all this with satisfaction. “You can just imagine how angry the Turks are,” he muttered. Too true.

The Russian Sukhois had done fierce damage to the Nusra bases, houses – the names of the “Nusrah front”, the “Army of Islam”, the “Ahrar al-Sham”, still spray-painted on what was left of their walls – blown apart by their missiles. Roads had been torn up, trees ripped apart, their huge trunks lying down the hillsides like giant skittles. And now the soldiers of what the Syrian army calls its Latakia Front sit on the grass by the roadside and brew tea, waving and smiling and – for the first time in years – tasting the fruits of victory.

Their field commander, a 50-year-old grey-haired general from Hama dressed in a black sports hat, a brand new Russian camouflage smock – “a gift from our friends,” he called it – and black boots, showed no hesitation in thanking the Russians. “Our honest friends showed how they stood with the Syrian army to fight terrorism,” he said. “They provide us with our cover in the field and on the ground. But air support doesn’t liberate land if there are no soldiers on the ground.”

The al-Nusra forces are clinging to this side of the frontier in what Syrian officers suspect is an attempt to provoke Syrian artillery to fire shells into Turkey itself. . .

Well, he could tell that to the American pilots in Iraq, couldn’t he, the pilots who have supposedly battered Isis over and over again for months but whose Iraqi allies seem incapable of advancing. Not so in northern Syria, where Syrian troops are moving rapidly eastwards in new Russian-made army trucks under Moscow’s air cover along the Turkish frontier from the old Syrian-Turkish border post at Kassab. The al-Nusra forces are clinging to this side of the frontier in what Syrian officers suspect is an attempt to provoke Syrian artillery to fire shells into Turkey itself – which the Syrians claim they have not done. Indeed, the field commander insisted that the Turks had fired into Syria and inflicted wounds on his own men.

It was, as we used to say in the old days of journalism, the first time a Western correspondent had visited this corner of the Syrian war since the Russians began air operations against the rebels. And it raised a host of intriguing questions. How was it, for example, that right next to the Turkish frontier post at Kassab, two spanking new roads lead from the Turkish side of the border into Syria?

The Syrians say that these roads – almost identical to those the Israelis used to build just inside the Lebanese frontier – were constructed by the Turks specifically for Nusra fighters to cross the frontier illegally, that the Turkish military not only tolerated but helped to build these little concrete highways down the hill into Syria.

And what else should one suppose when, in front of my own eyes, a small Turkish military patrol including an open truck of Turkish troops blithely passed the two new roads which are blocked by neither fences nor concrete blocks? A bunch of Syrian military intelligence men now live inside the Syrian post, although they have not yet painted over the rebel names that also litter the outside walls. Behind the border, you can see the white crescent-on-red of the Turkish flag.

But an intriguing tale is told of the recapture of the Syrian border post; of how former “Free Syrian Army” units – reincorporated into the Syrian army after their original desertion – were given the “honour” of carrying out the operation, of how two of their groups overwhelmed the Nusra men and restored Syria’s sovereignty on the northwest corner of its territory. The narrative, needless to say, tells a lot about the Syrian army’s portrayal of the “moderates” Messers Cameron and Obama like to talk about, although we must suppose that the infamous “fog of war” may cover all these exploits, at least until we have time to investigate the reality.

I walked up to the Turkish border post. “Welcome to Turkey,” a signpost said in Arabic, English, German and French, but there was no welcoming to be done. When I peered below the Turkish border guard offices, I saw only the bust of a man – thus was I met by the grim stare of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk.

And indeed, the founder of the Turkish state would have much to be grim about. The Syrians are now making their way along the frontier which – scarcely two weeks ago – the Turkish army threatened to invade. Across the bare surface of Dahih mountain, you can see the Syrian army’s tents pitched in lazy profusion. It was just after the capture of this hill, only a few hundred yards from a concrete Turkish police post, that the Turkish airforce shot down Russia’s Sukhoi bomber and set off the latest crisis in Russian-Turkish relations.

“Turkish revenge for our victory on the mountain,” the Syrian soldiers chorus. “The Turks must be going mad,” one of their colonels said. The wounded Russian crewman who was rescued after his plane crashed returned to duty at the big Russian air base at Latakia on the Syrian coastline just four days ago.

In hours of travelling along twisting mountain roads, past streams and lakes that are so reminiscent of Bosnia, I saw no sign of any Russian military personnel. There are plenty of Russians in western T-shirts in the big Afamia hotel – along with a six-man Moscow TV crew – in Latakia. And the Sukhois roar deafeningly over the main coastal highway, while off the coast of Tartous a large Russian warship moves like a ghost behind the sea fret two miles offshore. But this is no Afghanistan – not yet – and if Russian air controllers have personnel on the ground with Syrian troops, I did not see them.

Nor did I see any civilians in the wreckage of the villages across the Turkmen mountain. For these were Turkmen homes, most – though by no means all – supporters of whoever Turkey helped in the war against Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Damascus. Some have fled as refugees to Latakia itself; many others must have joined the refugee trek towards the Turkish border. The Syrians say they have buried all the dead Nusra fighters they found – no figures available, of course – and with Islamic rites (also, “of course”), but there must be other human beings dying across the valleys as the distant thump of shells echoes back to the Syrian army.

Indeed, it is a little disturbing to gaze across this haunted landscape with its ruined villages and the smell of unpicked oranges and the distant white and grey smoke blossoming on the opposite hillside because you must remind yourself that the war goes on, that victories – however successful and however committed the Kremlin may be – do not finish because one army breaks a cocktail of Islamist rebels along the Turkish frontier.

Many of the houses around al-Rabiaa appear to have been peppered by shrapnel from Russian air bombing and unexploded artillery and mortar ordnance lies across the fields. In one wrecked village, we had to veer sharply to the right to avoid an unexploded Grad missile, fired by Nusra, which had embedded itself, all grey steel and wires, in the middle of the street.

The Syrians themselves like to emphasise that their enemies are all foreigners – Turkmen from Turkey and Turkmenistan, Uigurs from China, civilians from Kyrgyzstan, although they know that Syrians, too, are out there across the valleys. “The Turks are spectacularly unhappy,” another officer said – he knew how clever his expression was in English – and expressed the view that “the Turks never expected the Syrian army would reach this point. They never guessed our strength and they know that their project here in Syria [the destruction of the regime] is collapsing.

“The Russians were very big here. They were very important, and I say this as a soldier on the Latakia front. But as you can see from the terrain – the mountains and rivers – this is a very complicated area for the military and the role of aircraft was less important as we fought our way through the valleys.”

Several officers spoke of a senior Turkish officer killed by Syrian shelling over the past few months – they name him as Major General Shahin Hassrat, who was supposedly at a meeting of Nusra fighters when the Syrian army targeted the building in which they had agreed to rendezvous. You can see the confidence of the Syrians now, walking up on to the hillsides to watch their own artillery bombardment, heedless of snipers.

But perhaps they know more than we do. Nusra has scarcely fired a mortar back at its enemies. No one stopped us filming the Syrian armour and the gun batteries standing beside the mountain roads. Indeed, there were several self-propelled guns whose sparkling camouflage paint and stylish, hull-clinging gun barrels suggested more gifts from Moscow had recently been arriving here.

And he went on to say that Syria was the land of “all peoples”, that the purpose of the “terrorists” and the Turks was to “sectarianise” the war. “We are a mosaic, our country comprises lots of nationalities – this is the secret of Syria.”

As for the general, he wished – like almost the entire government of Syria – to implicate Turkey in the “terrorist” attempts to destroy Syria. “The Turks actually brought Uigurs here and Turkmenistan people – with their families – to settle them here. This was their project. Our soldiers are now advancing right along the frontier wire and every advance forward squeezes the terrorists Turkey directly supports. And everyone who stands with us” – the general was talking about the Russians – “we are very grateful to.” And he went on to say that Syria was the land of “all peoples”, that the purpose of the “terrorists” and the Turks was to “sectarianise” the war. “We are a mosaic, our country comprises lots of nationalities – this is the secret of Syria.”

But can Syria be put back together again? The Syrian army is in the habit of talking again about a future state with all its borders intact, with the Isis capital of Raqqa again under its control and – of course – with President Bashar al-Assad as “the guarantee of the stability of Syria”. I pointed out to the general that he wore no identification or badge of rank on his Russian-made camouflage smock, and suggested that – unlike Admiral Nelson – he preferred not to make himself a target for snipers. He knew the story of the French sniper in the rigging. “Liberating our land is the most important medal we can wear,” he replied.

But how much of Syria can be liberated? What do the Turks now have up their sleeve? And Saudi Arabia? And Qatar? And Russia? And, indeed, what of Nusra and the various outfits that clung around al-Qaeda, some of whom – far to the east – transmogrified into Isis? There was no “Free Syrian Army” graffiti on the walls around al-Rabiaa, which suggested that David Cameron’s 70,000 “moderate” ghost soldiers did not cut much ice here.

But Isis is not dead. The Syrians know this as well as anyone, not least because they have real “boots on the ground”, and know after almost five years of fighting that the cult which still rules far away in Raqqa has a fearful habit of striking back.

The story of a teacher evicted from Raqqa illustrates so much about the conflict in Syria

Can Syria be put back together again? Soon life after Isis will have to be contemplated here

Isis supporters in Raqqa | AP

One response to “Syria: Robert Fisk reports from the front lines”

- Pingback: Syria: Robert Fisk reports from the front lines — Tony Seed’s Weblog | Free Political Prisoners in Iran